Newlands Mill

Newlands Mill Disaster 1882

Newlands Mill was one of many mills in Bradford in the 19th Century but prior to mills being built, quarrying and mining were one of the main industries in Bradford.

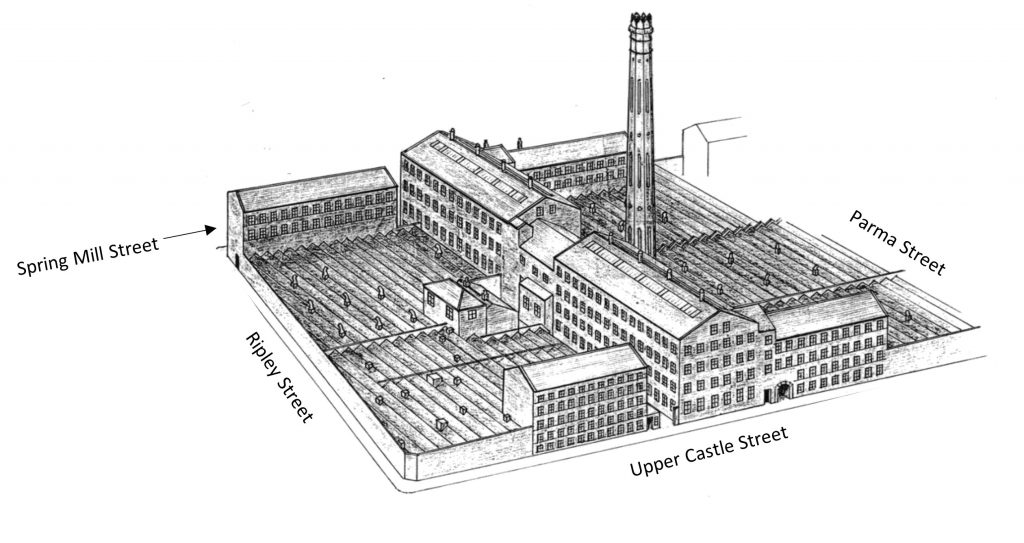

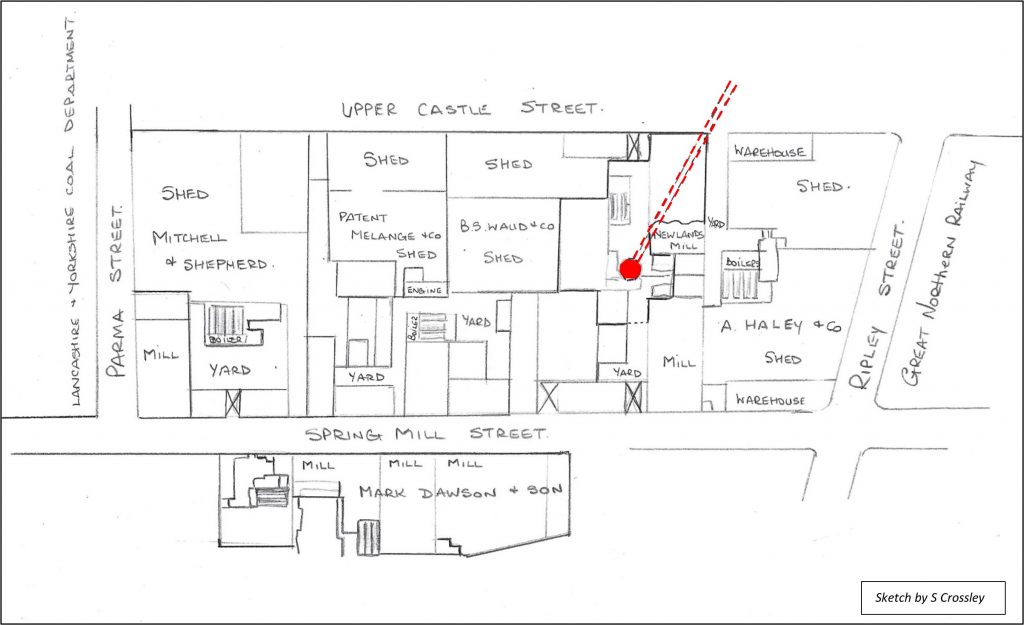

In the early 1860s Henry William Ripley purchased a green field site just off Manchester Road not far from the Ripley Dyeworks. Although this land had never been built on before, it had been used by coal and ironstone miners in years gone by and a seam of good quality coal had been worked down to a depth of about 60 feet. Henry Ripley began building a vast complex of mills, with warehouses, sheds, and a huge chimney, all of which would become known as “Ripley’s Mills”. This was a building project that would bring about the worst tragedy in Bradford’s industrial history.

The Ripley’s were just one of a number of rich and powerful families in Bradford during the Industrial Revolution of the 19th Century and the family also owned the large Ripley Dyeworks.

The mill complex covered a five-acre site and many different types of textile processing work would be carried out there – spinning, twisting, weaving to name a few. The chimney was the first thing to be built.

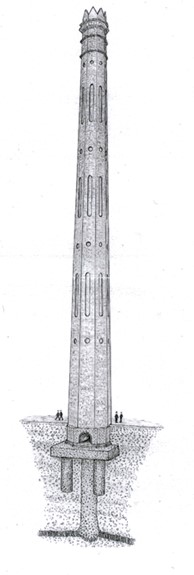

Plans for an octagonal chimney were supplied by a local company of Andrews and Delaunay and the chimney’s measurements were in proportion to its intended great height. At the base, the diameter was 24 feet and at the top 17 feet 6 inches. Building began in 1862 by John Moulson and Sons a well-established local company.

The actual site for the chimney structure had been a source of problems ever since building work began. The area where the foundations were to be built for the chimney had been used as an old pit shaft and the shaft had to be filled in with stones, timber wedges and cement mix. Originally Ripley had wanted his mill chimney to be the tallest in the area, standing at 100 yards high [just under 300 feet] but the foundations were too weak to support such a vast structure.

When the chimney had been raised to a height of 70 feet, the contractors were surprised to discover that it was not perfectly straight. An expert brought in by the owner, thought that the masonry was sound but that the foundations had given way. Another expert was summoned to remedy the defect and this was done by cutting through some of the masonry courses on one side of the chimney at about 50 feet up. This had the effect of bringing the chimney back very nearly to perpendicular. Building work was suspended to check for any further subsidence but none was found and building work continued.

Mr Ripley had issued instructions to his architects for the eight faces of the chimney to be embellished with recessed panels. Even though the builder stressed that the ornamentation would weaken the strength of the fabric of the chimney, Mr Ripley’s orders were carried out.

The top of the chimney was surmounted by an enormously heavy cornice, which was said to be a striking feature and this alone needed the use of more than 50 tonnes of ashlar [finely dressed stone]

When the building work was finally completed late in 1863, the octagonal chimney was a towering 255 feet tall [about 78 metres a similar height to Lister’s Mill Chimney] with an adjoining coal-fired boiler house which provided steam power to belt-drive the various spinning and twisting frames and looms etc.

The mill complex rapidly developed and soon the chimney was completely surrounded by mills and weaving sheds and one of these buildings was Newlands Mill, a 4-storey building with an attic.

The main entrance was in Upper Castle Street, just a short distance from Ripley Street. The premises were tenanted by Messrs. Haley and Company, who occupied the ground floor and the attic. A covered wooden walkway connecting the attic to the principal mill. Messrs. W Greenwood and Company, worsted spinners occupied the second and third storeys and finally the fourth floor was leased to Jonas Horsfall and Company.

Only three years later, in 1865, cracks appeared in the chimney and corrective repairs had to be carried out. Further cracks appeared in 1873 and again steeplejacks and building workers had to be brought in to correct the problems. By this time, the chimney had become quite a talking point in many shops, pubs, and workplaces around West Bowling, as many people feared it would topple over one day.

By 1882, the chimney was giving rise to concern once again. High winds caused the chimney to sway visibly and large cracks had appeared. Frequent falls of stone and lime smashed panes of glass in the mills below and one of the corners of the octagon on the south-east face of the chimney, about half-way up, developed a bulge.

A few days before Christmas 1882, the owners called in experts to inspect the chimney. These gentlemen determined that the outer shell was coming away from the inner lining but they felt there was no cause for alarm. However, it was decided to carry out necessary repairs over the Christmas period and Moulson began to erect scaffolding around the chimney. Further masonry continued to fall from the chimney, so a fence was erected around the base to reduce the risk of anyone being hit by falling debris.

Newlands Mill workers must have been looking forward to the Christmas festivities when the mill closed down for the brief holiday break on Friday 22 December. The following day steeplejacks arrived to get things ready for the repairs to correct the chimney’s bulge and falling masonry problems.

The weather during the Christmas period had been unusually severe, with heavy rain, a storm, hard frosts, and strong winds which stung the Bradford area. Mill workers returned to work at 6am on the morning of Thursday 27 December.

Just before 8am when the working people were just about to break for breakfast, three or four tons of stone fell from the chimney into the mill yard. The noise of the looms prevented people from hearing the crash. Some people did see the stone fall but as repairs were in progress, they didn’t think it was anything to worry about.

The disaster

At 8:00am the machinery was silenced and many of the employees left the premises to have their breakfasts but a hundred or so stayed behind. Disaster struck just before 8:10am.

A strong gust of wind hit the chimney and it tottered, bulged, and collapsed in a south-easterly direction across the centre of Newlands Mills

An eyewitness later told how the chimney “seemed to fall in a solid column for some little time, then it broke off at the bottom and fell upon the mill in two pieces”

The Bradford Observer reported that “for several minutes there was an appalling darkness and a continued crashing of crumbling ruins and then when the thick cloud of dust which arose had cleared away it was seen that the one end of the mill had been levelled to the ground and that an area of perhaps 400 sq. yards was covered with debris”.

Masonry, timber, and machinery were jumbled together in one mass and, at first sight, no sign of bodies, dead or alive could be seen.

Newlands Mill was almost completely razed to the ground. It had been cut through “as cleanly as if it had been done by a knife” Only an end section remained in which the spinning frames were left standing.

Scenes of extreme concern flowed throughout the district as the magnitude of the disaster became apparent. The great mass of stonework barely had time to settle before the area was attacked by frantic rescuers who desperately tore at the rubble in response to cries of distress from the injured and dying. Rescuers were soon joined by doctors, clergymen, officials of the corporation, the Fire Brigade, and a detachment of police under the charge of the Chief Constable.

About 30 people who had not been in direct line of the falling chimney, but had been struck by masonry, were quickly sent to the infirmary. Within an hour the first bodies – those of 6 young people had been brought out.

Most of the faces were blackened and covered with blood but some were strangely perfectly clean. In addition, there were many broken bones and some of the bodies were terribly mangled and crushed.

A nearby warehouse was set up to take the dead and as the day wore on, the temporary mortuary had taken in 22 bodies, while a further four people lay dead at the infirmary. Of those bodies that lay side by side covered in rough sacking only 14 were immediately claimed

The remaining bodies that had sustained mutilation “too horrible to be described” were in most cases identified only by means of their tattered clothing. By midnight, the “earnest work of rescuers” had removed about one-sixth of the debris, the late evening operations continued with the assistance of electric light, a dynamo-machine was brought from the nearby Ripley’s dyeworks.

Anxious crowds gathered at the gates of the infirmary on the morning of the catastrophe to witness countless injured work people being taken in.

During the afternoon the mayor, Alderman Frederick Priestman and Sir Edward Ripley visited the infirmary and later Sir Ripley sent a quantity of hothouse grapes and a small case of Eau-de Cologne for the benefit of the injured.

The search for those missing and the task of recovering bodies continued throughout Friday, the operation being done in two shifts of 150 men on each shift.

There were tales of horrifying discoveries by the men searching for bodies, with decapitation and crushing injuries being common. The bodies of Charles Smith aged 58 and his 11-year-old son Arthur were brought out together. The father was found in a “gently reposing posture” with his young son in his arms. Charles died from suffocation and his son from broken ribs. It was thought that the son was already dying when his father took him in his arms.

One 10-year-old boy David Charles Brewer cheated death as he had been trapped in the cellar of Newlands Mills when the chimney fell. His cries for help were heard by a joiner who dug into the ruins and rescued him. When asked what day he thought it was, David replied “About Tuesday”, in fact, it was Friday at 9pm and he had been trapped for over 37 hours.

Over the weekend and into the new year, 1883, the rescue operation continued. It was not until 3 January that the last body was recovered.

The last person to die from injuries sustained in the disaster was Grace Ellen Fawthrop, she died on 7 January at the infirmary. Her cause of death was entered into the official register as “Fracture of the skull and laceration of the brain caused by the fall of a chimney belonging to Sir Edward Ripley, Baronet and others, Trustees under the will of the late Sir Henry William Ripley Baronet at Newland Mills in Upper Castle Street in Bowling on the twenty-eighth day of December 1882”

The Inquest

The coroner, Mr James Hutchinson opened an inquest into the deaths on 29 December 1882. During the course of the inquiry, he had to adjourn the proceedings at least 15 times while the jury heard numerous accounts [often repetitive but sometime contradictory] of the disaster.

On 31 January 1883 after retiring for almost two hours the jury delivered its brief verdict.

“We find that the owners did all that non-practical men could reasonably be expected to do under the circumstances, and therefore we do not attach any blame to them or find them guilty of negligence and give as our verdict of Accident Death. We are of the opinion that the foundation was good, and that the fall of the chimney was partly due to the cutting, aided by the strong winds on that morning of the accident and regret that the works were not stopped during the repairs”

This inconsistent verdict caused a national sensation and the Bradford Observer, whilst refraining from comment, freely quoted the angry reaction of the provincial press.

The influential Birmingham Daily Mail was appalled and disgusted at the outcome of the inquiry into the disaster “which cost as many lives as a small battle” “ the old story, nobody to blame” it thundered.

“ A tall factory chimney, known to be in an unsafe condition and actually undergoing repair at the time of the accident, falls with a crash upon the buildings beneath, grinds them to ruins, kills 53 [sic] of the poor creatures who had to work there for their daily bread, and nobody to blame”.

The evidence offered by witnesses at the inquiry clearly indicated that collective responsibility for the disaster lay with certain persons and Mr Hutchinson hinted as much in his summing up.

“A more unsatisfactory finding has rarely been arrived at in a court of law” commented the Globe.

The Illustrated London News sincerely hoped that

“the relatives of those killed will be able to recover large pecuniary damages, either from the owner of the chimney, or from their immediate employers, for the affliction caused by what seems to be the mere result of culpable mismanagement; of no unforeseen accident but somebody’s shameful want of care”

The victims

54 Lives were lost due to the Newlands Mill Disaster – 41 were females and 13 were males, with an average age of 18 years, and 20 below the age of 15 years.

It seems ironic that the name of Sir Henry Ripley should be associated with the fearful ‘Ripley’s Mills’ catastrophe, for he was noted for his philanthropic outlook and it was said of him that “his desire was always for the improvement of the conditions of the poorer section of society”

In 1882, Sir Henry Ripley was given honour of handing to the Prince of Wales a gold key, which the future King Edward VII opened the Technical College. In November 1882 Sir Henry Ripley died at the age of 69 – less than two months before the chimney’s collapse.

We can only feel thankful that he was spared any knowledge of the shocking death toll amongst the “poorer section of society”

A number of the Newlands Mill disaster victims are at rest in Undercliffe Cemetery

Two brothers, George and Joseph Boldy are buried in the S section consecrated along with their parents Benjamin and Agnes, their brother Tempest and his wife Beatrice and their sister Martha Elizabeth. The headstone reads:

In loving member of George, son of Benjamin and Agnes Boldy of Bowling, age 16 years. Also, of Joseph Ellis, son of the above aged 12 years who were killed by the fall of a mill chimney at Bradford on Dec 28th 1882.

Sisters, Sarah Jane Burley [aged 17] and Lilly Burley [aged 14] also perished in the disaster. They had previously suffered the loss of their mother Elizabeth in 1875 with their father William marrying again that same year. The girls had four brothers. They are buried in P consecrated section of the cemetery.

Lavinia Cooper [aged 19] died leaving parents William and Mary Jane Cooper along with six siblings. She is buried in the L Consecrated section with her grandparents Joseph and Nancy Muff.

Sources

Mr John Jackson

British Newspaper Archive

The Bradford Observer

Illustrated London News Picture Library

Ancestry

West Bowling Local History Newsletter Production

Undercliffe Cemetery burial records

Research by Susan Crossley