Maurice Wilson

MAURICE WILSON (1898-1834)In Undercliffe Cemetery in a grave numbered C184 (Consecrated) are of the remains four young children: John William Pearson (died 01.12.1860 aged 22 months), and Mary, (died 05.12.1860 aged 3 years). There are also William Mitchell Pearson, ( 01.06.1875-02.06.1875) and Mary Jane Pearson (died 08.02.1878, aged 18 months) who are probably sister and brother. The grave also contains of Sarah Ambler (died 29.06.1874 aged 64 years). Sarah was the grandmother of the two later children but it is a mystery where John William and Mary fit into the family. They could be Sarah’s later children or her grandchildren.

Sarah Ambler had run an eatery in Market Street, Bradford with her only daughter Martha Ann (born in 1845). On 26 December 1864, Martha Ann married Timothy Pearson who was a fruit seller in Westgate. It was this couple who felt the despair of losing two children. Their eldest child, Sarah Elizabeth was born in 1866 and grew up to marry Mark Wilson from Bowling on 27 July 1892. A few days later her mother Martha Ann, brothers, Fred and Albert and sister Florence Louise left England for good to join Timothy and other members of the family in the United States. Although both Timothy and Martha Ann died in Oregon in 1910 and 1896 respectively, they are memorialized in Undercliffe Cemetery. It appears that only Sarah Elizabeth remained in England. Some of their children lived in San Francisco. The boys tended to remain in their father’s profession of produce retailers.ch

Mark Wilson was raised in Birch Street, Bowling and it is there that the couple settled and started their married life together. Mark was a worsted textile over looker; however, later he became a manufacturer in his own right operating out of Holme Top Mills. I doubt this couple ever thought that they would produce a son who led such a different and interesting life.

They had four sons, Fred (1895-1979), Victor (1895-1924), Maurice (1898-1934) and Stanley (1903- )

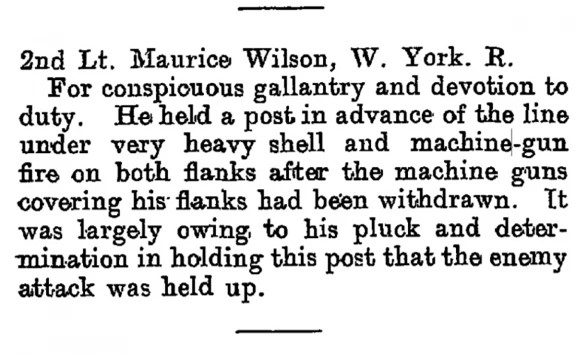

Maurice like most men of his generation entered the forces when the Great War began. He fought at Passendale and rose quickly through the ranks to the be 2nd Lieutenant and earned the Military Medal for his conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. At Meteren ( this is disputed. It may have been at Wytscaete) as the only uninjured officer he successfully single handedly took charge of a machine gun. His luck was not to last and later he was later badly wounded in his arm.

Once home he was blighted by his wound which would not heal. Denied a war pension and probably suffering from what today would be called PTSD, he became restless and travelled extensively. He tried every possible solution for his wound, both medical and religious. He heard of a healer who believed fasting and prayer could heal the body and allowed the practitioner to find a golden plane or higher plane of existence. It appeared to work for Maurice, although in reality it probably did not, and he became a keen advocate of this philosophy.

In 1922, he was living at 18 Cecil Avenue when he married Beatrice Hardy Slater. He is recorded as being a merchant and was probably employed at his late father’s mill. There appears to have been no children from this union and how and when the marriage ended is unknown but Maurice married again in New Zealand in 1926 to Ruby Russell. However, it is said that his true love was Enid Evans, the wife of Len Evans and they entered into a complicated love triangle. Therefore, it perhaps seems strange that he appointed Len his executor.

When he settled in New Zealand he a sold women’s clothing. This apparently was not the life for him as after reading about a failed attempt at climbing Everest in 1924, he decided that this was to be his quest. Those who failed the 1924 attempt were Mallory and Irvine who had perished on the mountain. Everyone advised him not to attempt the climb and the Government of the day, forbade his expedition. This seemed to make him more determined despite the fact that he had no climbing , climbing at altitude and appeared ignorant of what equipment he would need.

The first problem was how to get to Nepal. The solution was to fly there. Unfortunately this was something else of which he had no experience. He bought a second hand gypsy-moth from the Scarborough Flying Circus at a knock down price due to the existing damage, repainted her and named her the Ever Wrest. According to his flying instructor it took Maurice twice as long to gain his flying license than other students. His instructor told him that he would never reach Nepal. He proved him wrong but his intention to just fly to Nepal and crash onto the Everest as high as he could did not quite work out. His journey included a few extra adventures starting with a very public crash into a field near Bradford. He liked the attention of the press and positively encouraged it. He had such an up-beat attitude it is unknown whether he was embarrassed by this initial set back or considered abandoning the whole expedition.

As it happened he continued with his preparations and set off in 1933. The British Government made it difficult for him to get to his destination and with the assistance of other countries arranged for him to be arrested in Tunisia, on arrival in Cairo he was informed that he had been refused permission to cross Persia. He was then turned around in Bahrain where he was forbidden to refuel. He told the officials that he would return home if they allowed him to refuel. They allowed him to do so but once he was airborne, he changed direction and headed for India.

The most westerly airstrip in India was at the very furthest range for the plane. He made it with the fuel gauge showing zero. He refueled and flew further to Lalbalu where he was forbidden to fly over Nepal and his plane was impounded. He was denied permission to enter Nepal on foot so spent the winter in Darjeeling. He met three Sherpa’s who had been on Rutledge’s 1933 attempt at the summit. Disguised as an ailing monk who was deaf and dumb he walked the last 300 miles into Tibet reaching the Rongbuk Monastery in April where they were warmly welcome.

His first attempt ended in failure. He was attempting the climb alone with unsuitable clothing and a 45pound ruck sack containing his lucky flag of friendship, a broken altimeter , a Buddhist text and a pick axe but no crampons. On his climb he found some crampons which would have been of great assistance but he just through them away.

He wrote in his diary about his first failed attempt, “Dammed bad luck”. Of the three Sherpa’s he had met when he first arrived in India, two agreed to show him the right route. It was hard going as normally there would be a greater number of Sherpas and the weather was poor. Things perked up at Camp III when they found some leftover Fortnum & Mason food which caused Maurice to break his fast. Energized he pressed on in his brocaded blue mantle with gold buttons and 12 feet of red silk scarf. His progress was good although he did cause an avalanche which sent him tumbling 200 feet down hill causing him to break ribs which required him to rest up for a few weeks. He had sought no information or expertise about climbing at high altitudes which probably sealed his fate as he may have been suffering with damage to his lungs.

Eventually his Sherpas left and Maurice gave one his pony. Undeterred, Maurice pressed on and reached over twenty-two thousand feet (the mountain is 29,029 feet above sea level). His body was found a year later by climbers, his mantle and scarf gone he was dressed in a mauve jumper, cream slacks and lightweight socks. His beloved green diary was in the rucksack and the last entry was on the 31 May: “Off again, gorgeous day”. He had penned a final letter to his beloved Enid in which he said, “Some of us go looking for it, some of us wait for it to call us up”. His exact date of death is unknown.

He was buried in the remnants of his tent in a crevasse from which he periodically appears depending on the season.

Sources:

• Births marriage and death records.

• 1916 London Gazette supplement.

• Census records

• Article by Jane Fryer, Daily Mail 23/11/2020

• Yorkshire Evening Post

• Leeds Mercury

Deborah Stirling, Researcher.